- Field Notes

- Posts

- A strange situation where cutting pollution made pollution worse

A strange situation where cutting pollution made pollution worse

And why the best policy for South Korea is still to keep cutting pollution!

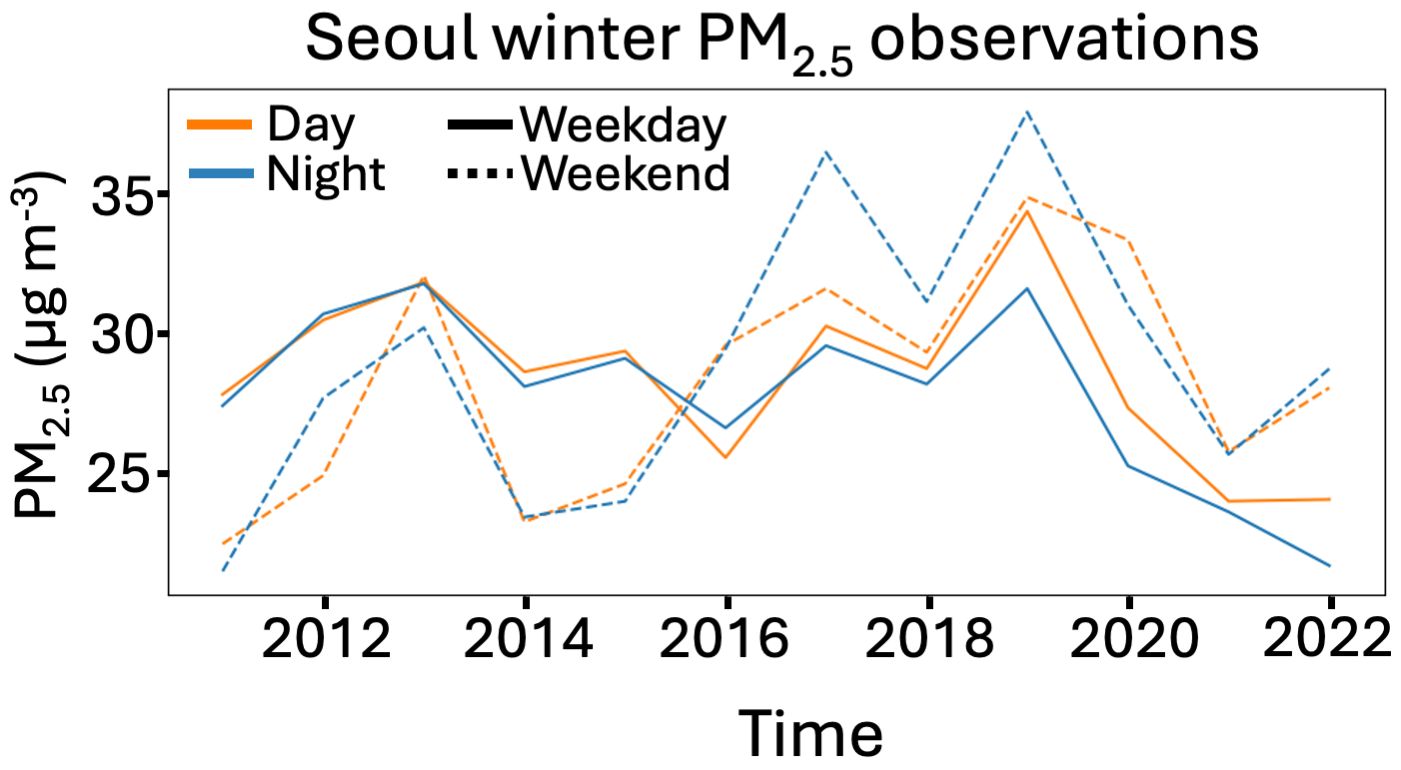

A couple months ago, a paper I led was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters (read here for free). We considered a strange case in South Korea where a major air pollutant — fine particulate matter, or PM2.5 — got worse, even as the pollutant emissions which drive PM2.5 formation fell substantially. What was especially strange is that PM2.5 only got worse in the winter, only over the 2015-2019 period, and the worst air quality degradation happened at night and on the weekends. Intuitively, this doesn’t make much sense. People drive to work and school more during the week than on the weekends; big emitters like factories also tend to be more active during the week. Certainly these sources are larger during the day than at night. Regulators also made sure that emissions cuts were steady over the time period; however, despite this, the the magnitude and even the sign of PM2.5 trends changed dramatically. What was going on?

Seoul particulate matter trends in winter over time. Pollution gets worse in the 2015-19 period, especially at night (blue) and on weekends (dotted)

The question isn’t a mere scientific curiosity (though chemically it turns out to be very interesting). PM2.5 is responsible for some four million deaths per year; fine particles can penetrate deep into the lungs, the blood, and even the brain and cause health problems in just about every system in the body. In Durham, NC, where I am currently writing this email, PM2.5 exposure reduces life expectancy by about three months. Because there is no safe exposure level, we want to reduce the amount of PM2.5 in the atmosphere to the lowest level possible.

First, some background: PM2.5 is both a primary pollutant, in that sometimes it is emitted directly into the atmosphere (think a smoky campfire), as well as a secondary pollutant, formed from chemical reactions in the atmosphere. Early regulations in South Korea were very successful in reducing primary forms of PM2.5, in part because these tend to be easy to clean up — basic regulations on car tailpipes go a long way. As that primary PM2.5 became less important, secondary PM2.5 became more important. Because secondary PM2.5 forms through chemical reactions, non-linear, complex, and counterintuitive behavior can emerge that isn’t present with directly-emitted primary PM2.5. So, to understand the strange air quality patterns in South Korea, we need to learn two bits of chemistry: (1) the thermodynamics of PM2.5 formation, and (2) the role of the nitrate radical in atmospheric oxidation.

Don’t worry! There will be pictures.

The thermodynamics of particulate nitrate

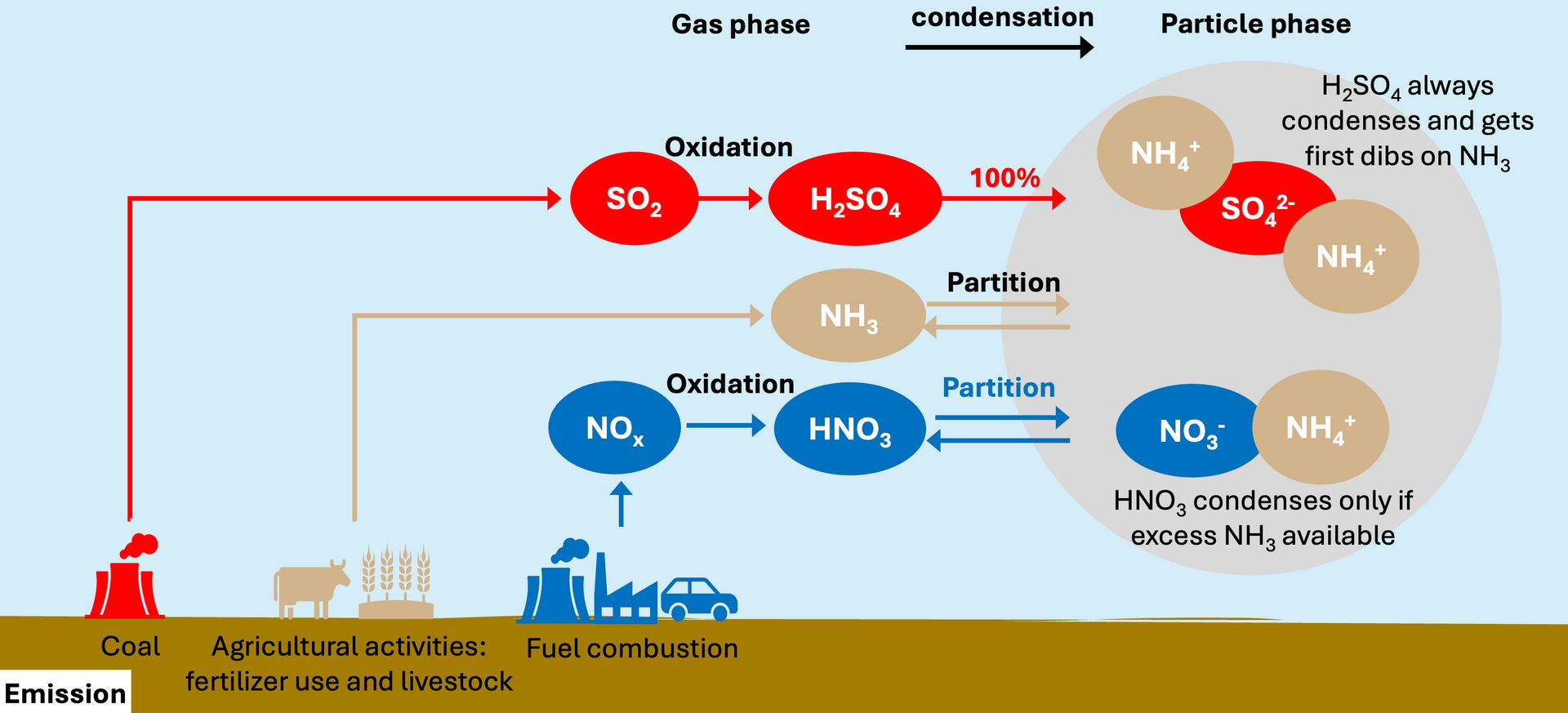

There is a lot of junk in PM2.5, but for our purposes we will focus on four major components: sulfate, nitrate, ammonium, and organic matter. The first three compose the bulk of inorganic PM2.5, and we’ll focus on them in this section. Sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium follow a simple but non-linear set of rules, which can give rise to some not-so-simple results. These rules are summarized in this figure, which we’ll work through in the bullets below.

A diagram of sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium thermodynamics governing inorganic particulate matter. This figure is based off one made by Ruijun Dang.

Human activities release gas-phase pollutants into the atmosphere, which go on to participate in chemical reactions. Our atmosphere is an oxidizer, which for our purposes means that it puts O’s on things.

Coal burning releases SO2, which the atmosphere oxidizes into sulfuric acid (H2SO4), as in the top red line of the diagram. Sulfuric acid has very low volatility, which means that it really wants to condense into small particles of sulfate (SO42- ). In fact, it pretty much always condenses, and very quickly.

In South Korea, regulators aggressively targeted SO2, leading to strong sulfate reductions since 2015.

Agricultural activities release ammonia (NH3). Ammonia will condense into ammonium (NH4+ ) to neutralize the sulfate already in the particle phase (two ammoniums for each sulfate). Ammonia has not been subject to substantial regulations.

Any form of hot burning will release nitrogen oxides (NOx), which the atmosphere oxidizes into nitric acid (HNO3), as in the bottom blue line of the diagram. Nitric acid has higher volatility than sulfuric acid, so it’s fine staying in the gas phase if it must. Nitric acid only condenses into particulate nitrate (NO3- ) if there is excess ammonium left over after sulfate is neutralized.

In South Korea, regulators also targeted NOx, leading to reductions in nitric acid (HNO3).

Nitric acid also will stay in the gas phase if it is too warm, or not humid enough. As a result, nitrate in South Korea is very important in winter and less so in other seasons.

That last point is very important for our study, because we are trying to explain unusual PM2.5 behavior in winter. This makes nitrate a potential culprit behind our counterintuitive trends. Indeed, as the below observations show, nitrate explains the 2019 peak in PM2.5 and subsequent decline. Why is this?

Observed trends in winter (December-January-February) composition of fine particulate matter in Seoul. OM means organic matter, while BC is black carbon (soot).

First, there is a mass effect that occurs when sulfate falls and nitrate is ready to replace it, as is the case in South Korea. Ammonium nitrate is, molecule-for-molecule, heavier than the ammonium sulfate it replaces. In this case, sulfate reductions liberate ammonium to neutralize newly-condensed nitrate. However, this effect alone is not sufficient to explain the increase in nitrate prior to 2019 (that will be covered in the next section).

Second, the non-linear behavior of nitrate implies that this kind of pollution will be sensitive to different forms of regulation depending on the atmospheric state. The brief gloss of inorganic aerosol thermodynamics I gave in the bullets earlier suggests that particulate nitrate can either be ammonia-limited or NOx-limited. In the ammonia-limited case, there is plenty of nitric acid sitting in the gas phase, ready to condense into nitrate, but there isn’t enough ammonium available to neutralize it. In this regime, regulations cutting NOx will have no effect on PM2.5 because cuts will just impact gas-phase nitric acid. This describes South Korea prior to 2019. Regulations successfully reduced sulfate, as shown in the sand chart above, but nitrate was unaffected (and actually increased).

However, in 2019, my colleague Yujin Oak has shown that particulate nitrate transitioned into a NOx-limited regime. This means that regulations cut NOx to such an extent that ammonia was now in excess, remaining in the gas phase, with all available nitric acid condensed into particulate matter. Now, every bit of NOx that regulators cut translates directly into a cut in particulate nitrate. This is fantastic news!

However, our story isn’t over yet. I suggested that the mass effect does not fully explain the increase in nitrate prior to 2019, and we also haven’t explained these strange weekend and nighttime effects. It turns out these effects can be explained by more NOx weirdness, this time in gas-phase radical chemistry.

The nitrate radical

The nitric acid story I have been telling you so far only really takes place during the daytime. At night, a whole different kind of chemistry can take place, as shown in the figure below. During the day, the hydroxyl radical (OH) is responsible for oxidizing NOx into nitric acid. However, OH requires sunlight. Instead, at night a highly-reactive compound called the nitrate radical (NO3) is available to wreak havoc. Like a vampire, NO3 wilts in sunlight but can go on an oxidation prowl at night. In particular, as shown on the right side of the diagram, the nitrate radical can form both particulate nitrate and organic matter.

The nitrate radical is an alkene’s worst nightmare.

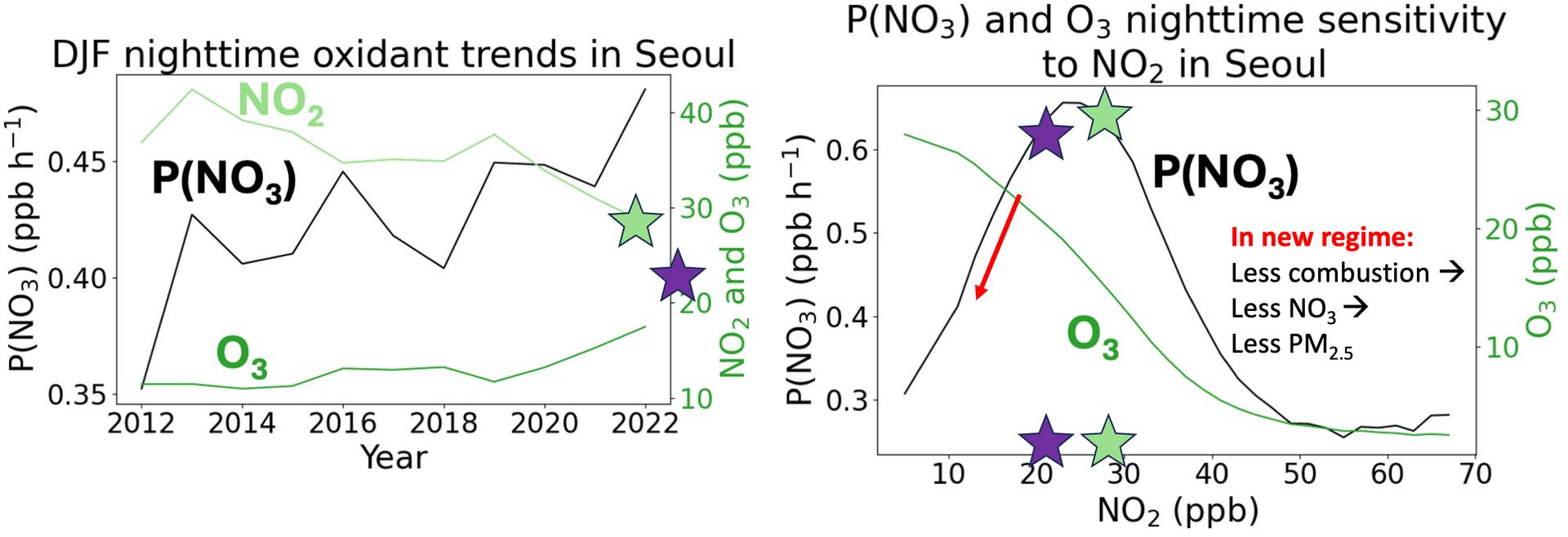

The nitrate radical is formed when NO2 (the main component of NOx) reacts with ozone (O3). Ozone requires light to form, so at night it isn’t replenished and can reach very low levels. As a result, there is an observed optimum trade-off between O3 and NO2, as shown below. At low NO2 levels (left side of plot), O3 is elevated (green line); the opposite is also true (when NO2 is high, O3 is titrated to almost nothing). This means that the production rate of the nitrate radical, labeled P(NO3), is maximized somewhere in the middle, when there is both abundant O3 and NO2. I show this “P(NO3) hill” below.

The goldilocks zone of nitrate radical production takes place at about 25 ppb of NO2, at the crest of our P(NO3) hill.

The atmosphere in South Korea started at the far right of the above plot, because NO2 pollution was very substantial. As Korean regulators cut NOx emissions, NO2 fell both during the day and at night, as shown in the left side of the below figure. However, this fall in NO2 came with an increase in nighttime ozone, which led the production rate of the nitrate radical P(NO3) to rapidly accelerate. We are climbing our P(NO3) radical production hill from the right.

Cuts in nighttime NO2 led us to climb the P(NO3) hill from the right, increasing the availability of the nitrate radical to form PM2.5

And indeed, when we plot an observed timeseries of the production rate of the nitrate radical (P(NO3); below, at left), we see that it increases over our time period of interest. Remember that more nitrate radical means more PM2.5 (particularly nitrate and organic matter). This helps us explain why PM2.5 trends from the very start of this post were worst at night, with the nitrate radical comes out to feast on double bonds.

As NO2 has fallen, nitrate radical production P(NO3) has increased, leading to a PM2.5 increase.

However, we still haven’t explained that pesky weekend effect. On weekends, there is generally less combustion, leading to less NOx. However, if we are on the right side of our P(NO3) hill, this will actually increase NO3 and thus PM2.5, as shown below. The paper goes through a lot more evidence for how we know this is happening, if you are curious.

When we are on the right side of the P(NO3) hill, reductions in combustion on the weekends will counterintuitively increase NO3, and thus PM2.5.

There is an upside in all of this. Just as in the previous section, where regulators cut NOx for a long time before the atmosphere transitioned to a regime where PM2.5 could respond, we are approaching a new regime where further cuts to NOx will lead to rapid reductions in the nitrate radical. The P(NO3) hill crests at around 25 ppb of NO2, which South Korea was approaching in 2022 (the green star below). Further cuts in NO2, to the level denoted by the hypothetical purple star, would put us on the other side of the hill. When that happens, both nitrate and organic components of PM2.5 will fall in line with emissions cuts. Give it a few years, and we’ll see if I’m right!

After NO2 levels fall below 25 ppb in South Korea, the production rate of the nitrate radical will finally fall in line with regulations.

To summarize the key take-aways from this study:

Particulate nitrate explains 2015-19 winter degradation in Seoul PM2.5, but improves in response to NOx controls beginning in 2019. This is because the atmosphere in South Korea has transitioned from an ammonia-limited to a NOx-limited regime in response to emissions cuts. However, this transition took years of regulation before it could materialize!

The nitrate radical explains PM2.5 degradation at night and on weekends despite lower emissions of NOx. This is because we have to climb the P(NO3) hill before regulatory benefits materialize.

Achieving the 25 ppb NO2 threshold will allow PM2.5 to decrease in line with emissions controls, as the P(NO3) rate will finally fall in line with emissions cuts.

Thanks for making it to the end of this marathon post! May your night air be clean and free of any oxidizing monsters.